Jeffrey A. Singer, Terence Kealey, and Bautista Vivanco

Since the publication of three books — Gary Taubes’s Good Calories, Bad Calories (2007), Michael Pollan’s In Defense of Food (2008), and Nina Teicholz’s Big Fat Surprise (2014) — it has become common to joke that there’s nothing wrong with the standard food pyramid as long as you turn it upside down.

The traditional pyramid placed carbohydrates such as bread and rice at the bottom (meaning they should be our staples), with protein foods halfway up, and fats at the narrow tip at the top of the pyramid (meaning they should be eaten sparingly). But the joke has now been embodied in the recent release by the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Agriculture (USDA) of their joint Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030. This is the latest version of their five-year publication that started with Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 1980—and it indeed inverts the pyramid, suggesting we should eat lots of fats and proteins while avoiding carbohydrates. What are we to make of this?

From Nutrition Science to Political Branding

Well, this is politicized science. For all their past sins, the Dietary Guidelines were at least presented as the product of a consistent, cross-administration, evidence-review process—not as a trophy for whichever party happened to be in power. The 2025–2030 edition changes that. In their introduction, HHS Secretary Kennedy and Agriculture Secretary Rollins openly promote the Guidelines as part of the Trump administration’s “Make America Healthy Again” agenda and a restoration of “common sense.” That framing isn’t subtle—and it isn’t technocratic. It’s a declaration that nutrition guidance is now being treated as an ideological project. When a government science document is marketed like a campaign plank, you don’t have to squint very hard to see politics displacing evidence.

Once you see the Guidelines being pitched this way, an obvious question arises: if their authors are willing to wrap scientific advice in overt political branding and sweeping policy rhetoric, why should anyone place special trust in their judgment about something as complex and contested as nutrition science? Neither Kennedy nor Rollins is a nutrition researcher, and neither has any special claim to expertise here. What they do have is political authority—and in this document, they use it to ask the public to take “scientific integrity” on faith. In science, authority is supposed to flow from evidence—not the other way around.

A Half-Century of Official Error

And we have good reason to be skeptical. The federal government’s track record on nutrition advice is, to put it kindly, not reassuring. The modern era of dietary guidance began in 1977, when the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs issued its Dietary Goals for the United States. Until then, federal nutrition policy had mainly focused on undernutrition. But by the late 1970s, policymakers believed that the rise of heart disease was largely driven by excessive consumption of cholesterol and saturated fat. Their solution was to encourage Americans to reduce fat intake and increase carbohydrate consumption—a change that would influence federal dietary guidelines and shape the American diet for many years.

Even at that time, the theory behind this pivot—that saturated fat and cholesterol were the main causes of heart disease and that Americans should largely replace them with carbohydrates—was unproven and hotly debated. Its most influential supporter was Ancel Keys, a physiologist at the University of Minnesota, who argued starting in the 1950s that dietary fat was the main culprit. The evidence he relied on was mostly cross-country correlation: countries that consumed more fat seemed to have higher rates of heart disease. Japan, where fat made up about 7 percent of calories, had very low rates; the United States, where it was closer to 40 percent, had much higher rates, with death rates among middle-aged men increasing from roughly 0.5 per thousand to nearly 7 per thousand.

But even in the 1950s, this story was already starting to unravel. In 1957, Jacob Yerushalmy and Herman Hilleboe demonstrated that the link between diet and heart disease was at least as strong—or stronger—for animal protein and total calorie intake than for fat alone, and that all of these factors closely correlated with income. In other words, Keys’ well-known correlations did not solely implicate fat, nor did they definitively establish causation.

Other researchers were exploring different ideas. That same year, the British physiologist John Yudkin reported that sugar intake had a stronger link to heart disease than fat, and he later warned, in Pure, White and Deadly, that refined sugar—not meat, cheese, or dairy—was the real dietary villain. Even Keys himself eventually admitted that dietary cholesterol was not the main problem, shifting his focus to saturated fat instead. And in 1970, Richard Doll—the epidemiologist who helped prove that smoking causes lung cancer—emphasized the central role of cigarette smoking in causing heart attacks.

Yet federal policy continued as if these debates never happened. Although Keys had stopped blaming dietary cholesterol by the mid-1950s, it wasn’t until 2015 that the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee finally acknowledged that “cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption,” effectively restoring foods like eggs and shellfish after decades of nutritional exile. For nearly fifty years, the official guidance on cholesterol was simply incorrect. In the rush to vilify saturated fat, policymakers and industry alike embraced “vegetable oils” and low-fat processed foods, which contributed to widespread consumption of partially hydrogenated oils—trans fats that we now know are clearly harmful.

Even worse, this entire structure was built on surprisingly little experimental evidence. By the time the Senate committee released its Dietary Goals in 1977, several randomized trials had already tested whether lowering total and saturated fat actually reduced mortality, and they showed no benefit. A later review by Zoë Harcombe and her colleagues put the point bluntly: the government gave dietary recommendations to 220 million Americans “in the absence of supporting evidence from randomized controlled trials.”

This was not a secret at the time. The American Medical Association warned in 1977 that “the evidence for assuming that benefits are to be derived from the adoption of such universal dietary goals is not conclusive, and there is potential for harmful effects.” When challenged on the shaky scientific foundation of the Guidelines, Senator George McGovern famously replied that “Senators do not have the luxury that the research scientist does of waiting until every last shred of evidence is in.”

In fact, the opposite is closer to the truth. Scientists are supposed to live with uncertainty; politicians should not be issuing nationwide health advice until the evidence is strong—precisely because the costs of being wrong are borne by everyone else. In 1977, they were wrong.

The Rhetoric of Crisis

In their introduction to the 2025–2030 Guidelines, the two secretaries state that “the United States is amid a health emergency,” noting that nearly 90 percent of health care spending goes toward treating chronic disease, which they describe as the predictable result of the Standard American Diet and a sedentary lifestyle. That rhetoric carries a lot of weight. The United States, like every wealthy nation, has experienced a dramatic rise in life expectancy over the past century and a half—an increase so consistent that, for much of the period since the mid-19th century, life expectancy increased by roughly three months each year.

The recent decline since 2019 is real, but it was mainly caused by COVID, overdoses, and other “deaths of despair,” rather than a sudden spike in diet-related chronic disease. No matter our health issues, this doesn’t resemble a civilization-wide nutritional emergency.

Should the State Be Your Dietitian?

Do Americans need good dietary advice? Of course. Should the federal government be in the business of giving it out? That’s far less obvious. Thomas Jefferson warned in 1787 that “were the government to prescribe to us our medicine and diet, our bodies would be in such keeping as our souls are now.” He was making a deeper point about the limits of political authority—especially in areas filled with uncertainty and individual differences.

To be fair, the current version of the Guidelines is clearly better than many previous ones. The Guidelines’ updated, more nuanced approach to alcohol is also a welcome change from public health’s recent trend toward strictness. The risks and benefits of alcohol consumption vary depending on age, context, and outcome, and the evidence is genuinely mixed and sometimes conflicting. Recognizing that tradeoffs are personal is not a failure of public health—it’s a return to honesty.

The new Guidelines reflect the influence of critics such as Nina Teicholz and the Nutrition Coalition, who have spent years advocating a long-overdue reexamination of low-fat orthodoxy. Gary Taubes would likely agree with much of this course correction. Michael Pollan, famous for “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants,” probably less so. That disagreement isn’t a bug—it’s a feature of a field where genuine scientific uncertainty remains.

And that is precisely the problem with wrapping nutrition advice in the aura of official, government-certified truth. As Teicholz documented in Big Fat Surprise, the history of nutrition science is riddled with groupthink, career incentives, funding pressures, and institutional inertia. It is telling that it took a handful of journalists—not the nutrition establishment itself—to finally puncture the 40-year reign of the low-fat dogma. In a field this contested, “consensus” is often just yesterday’s error with better branding.

That’s reason enough to ask a more fundamental question: why do we need the federal government telling us how it thinks we should eat? There is no one right answer, but when the federal government makes recommendations, health care providers and patients often treat them as authoritative. Humans have survived for thousands of years without governments telling them what and how to eat. Government should stay out of this and let autonomous adults decide for themselves—consulting the experts and sources they trust—what and how to eat.

A Different Pyramid: Reversing the Direction of Authority

The 2025–2030 Guidelines are almost certainly less harmful than many of their predecessors. But they cannot possibly bear the epistemic weight their authors place on them. The best we can reasonably ask of the federal government is not to issue dietary commandments, but to collect and summarize the best available evidence—and then leave individuals, clinicians, and genuinely independent scientific institutions to exercise judgment. In nutrition, as in much else, humility is not a weakness. It’s the beginning of wisdom.

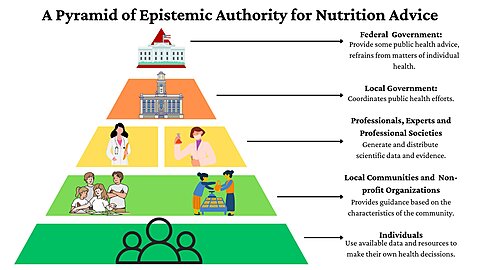

We conclude by proposing a different pyramid—not a pyramid of foods, but a pyramid of epistemic authority—one that places individuals and evidence at the base, communities and shared experience above them, professionals and expert institutions higher up, and government agencies at the narrow tip, where they belong: not absent, but least authoritative.